21-04-2022

Digital nomads: a bet for residential tourism in Costa Rica?

Arturo Silva Lucas | Alba SudA new law in Costa Rica seeks to attract digital nomads. The increase in the demand for second homeowners housing may lead to the exacerbation of new real estate tourism conflicts on the coasts.

On August 11, 2021, the President of the Republic Carlos Alvarado signed law 22,215 for the attraction of foreign digital nomads to Costa Rica in the company of the then Minister of Tourism Gustavo Segura. The initiative is one of the main proposals not only for the reactivation of tourism but also for the economic reactivation of the country after the pandemic. Even though the government signed the law eight months ago, to date it lacks an administrative statute that regulates its application. This has generated the annoyance of business chambers linked to the tourism and real estate sector, to the point that they have threatened the executive with legal measures if there is no advance with the statute as soon as possible.

Through tax exemptions and immigration privileges for high-income foreigners, the new law is presented as an example of trickle-down economics in rural destinations. However, the text omits any reference to territorial development or planning that accompanies the possible increase in the demand for exclusive tourist housing in destinations associated with real estate bubbles. Media such as The New York Times and the Financial Times have recently written about the tourist real estate problem in Costa Rica. Articles in these media have pointed out the real estate debauchery in sun and beach destinations as one of the threats facing the environmental reputation that Costa Rica enjoys in the world.

The new law has been conceived solely as a window for a foreign currency designed to satisfy macro indicators. It lacks any type of dialogue or understanding with areas affected by real estate speculation. This repositions rural regions as passive recipients of external investment, awaiting initiatives that arise from the country’s capital or interest groups.

The road of Law 22,215

The “Law to Attract Workers and Remote Service Providers of an International Character”, file 22,215, known as the law for the attraction of digital nomads, was presented by the senator of the Liberación Nacional Party Carlos Ricardo Benavides in September 2020. Benavides's curriculum highlights having been minister of tourism twice and president of the Executive Committee of the World Tourism Organization between 2008 and 2010. In 2013 his name was involved in an irregular concession of Isla Plata in the province of Guanacaste to develop a tourist complex in the name of a company in which a relative of Benavides was listed. The concession was finally revoked due to procedural defects.

The bill for the attraction of digital nomads was approved on the legislative floor on July 13, 2021, with 34 votes in favor, 5 against, and 18 absences. Despite the time that the file was in the legislative stream, it did not have any significant opposition. Some objections from legislators pointed out that the tax exception regime for foreigners represents an unfair preference to nationals, in addition to being able to make it easier for criminal groups to legitimize their capital. Despite these criticisms, in response, the Department of Studies, References, and Technical Services of the Legislative Assembly in its report AL-DEST-IIN-077-2020 concluded that Costa Rica lacks tools to control the income from activities based in another country.

Las Catalinas. Source: Arturo Silva.

The text that was finally approved, and then signed by the president, condenses the main guidelines of the law into ten pages. The leadership and coordination are in charge of the General Directorate of Migration and Foreigners (DGME). They will receive applications for a new migratory condition called Non-Resident-Stay Subcategory, which is defined as:

a foreign person who provides paid services remotely, subordinated or not, using a computer, telecommunications, or similar means, in favor of a natural or legal person who is abroad, for which he receives a payment or remuneration from the outside. (Legislative Assembly, 2020: 2).

The benefits include total exemption from income tax and exemption of all taxes on the importation of personal work equipment for up to a maximum of two years. The person who wishes to apply for this benefit must prove that they have a minimum monthly income of three thousand dollars or a combined income of four thousand dollars minimum per month if they come with their family group. The Customs Office of the Ministry of Treasury is in charge of certifying work equipment for personal use and the Ministry carries out investigations if there are suspicions of misuse of fiscal benefits. For its part, the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT) deals only with promotion and marketing tasks. The law authorizes the ICT to sign public-private agreements, strategic alliances, and incentive programs with national and international entities. And when it deems it necessary to exchange information with the DGME for the efficient achievement of the goals of the new law.

In the final text of ten pages, there is nothing that suggests any type of study or information that allows supposing that at the time of drafting the law there was some reflection of a territorial nature. For example, answers to questions such as: which destinations in Costa Rica would be desired by digital nomads? How has the experience of host communities with this type of tourist migrant been so far? Is there territorial planning in these destinations and what is the status of access to essential services such as water? What type of housing is associated with this tourist profile? How would the law affect the real estate market in the short term, and in relation to the price of housing in rural areas? Do rural municipalities have the technical and professional capacities to deal with the increase in environmental permits and controls for new housing projects?

The idea of facilitating the entry of digital nomads is mainly defended by various business chambers and senator Benavides. In testimonies reproduced by the press, Benavides affirms that the arrival of long-stay tourists is beneficial for rural areas due to the large number of resources that they invest. Tourism businessman Barry Roberts, on behalf of the Tourism for Costa Rica organization, points out that each digital nomad generates fourteen times more than a common tourist. The delay in the regulation, says Roberts, forces them to be on the verge of taking legal action against the government.

Source: Arturo Silva.

As a curious twist of fate, in the last two months, Benavides and the business chambers have been dissatisfied with the final version signed by the president. For senator Benavides, the obligation that each application must be apostilled and present documents proving economic income will drive away digital nomads. These criticisms are shared by the National Chamber of Tourism (CANATUR), which considers it inappropriate to request "excessive information". Benavides and CANATUR maintain that these observations are shared by the Costa Rican Investment Promotion Agency (CINDE), the Costa Rican Foreign Trade Promoter (PROCOMER), the Chamber of Construction, the Chamber of Hotels, the Costa Rican Union of Business Chambers (UCCAEP), the Real Estate Development Council, the Bar Association, among others.

The gap between the expectations of an increase in foreign exchange without a proposal for territorial development, which considers the consequences that have arisen up to now, should not be a minor detail. It should be one of the most important areas of attention for the Costa Rican brand and its tourism policy. A problem that important international press already recognize.

The problem

This March 13, in an article titled “Trouble in Costa Rica’s eco-paradise as homebuyers heat up market”, the Financial Times stated that the popularity of the coast is driving up land prices creating problems in wild areas. The article describes the weak controls that exist in Costa Rica as one of the causes of the real estate disorder in rural areas. It is argued that the Costa Rican coast follows the same path that led Los Angeles and New York to have a housing market unattainable for most of the population.

In the same vein, on March 30, The New York Times published an interview with Craig Studnicky, director of ISG World real estate agency with operations in the country. In it, Studnicky explained how for several years Costa Rica, especially the entire Pacific coast, has been the new Miami for real estate agencies. He gives as an example the sale of a three-bedroom house in Tamarindo beach, Guanacaste, for 890,000 dollars. When asked about the new law to attract digital nomads, Studnicky did not skimp on his praise “…they are rolling out the red carpet for us Americans, that is why I affectionately refer to Costa Rica as the 52nd state”. Studnicky has great expectations with the new law, thanks to which he has managed to place new housing projects in the South Pacific abroad with unit value of up to 1.5 million dollars.

But what is residential tourism? It’s the financialization of rural land in destinations with tourist value in favor of new urban land. It’s made possible through the action in the territory of financial intermediaries who capture profits resulting from the equation “buy low, sell high”. For it to be a profitable business model, residential tourism must continually consume new spaces, trying to sell at a price that allows them to have an ever-increasing profit margin. In cases such as the Costa Rican coasts, the financial intermediary is recognized in the figure of the real estate agent. In turn he relocates lots and properties in buyers’ circuits outside the local market. That’s why it is usual to recognize a significant number of foreigners with greater purchasing power in residential tourism investment niches.

Antonio Aledo and Antonio Miguel Nogués-Pedregal (2019) state that this is possible when there are weak planning policies or neoliberal territorial management policies. For these authors, residential tourism is explained by the trinomial “tourism – urbanism – migrations”. In this scheme, tourism is the axis with the least weight, because its main activity is to build houses for new residents or seasonal visitors with a weak sense of locality. In addition, residential tourism is not an instrument of local development since its precisely constituted on spatial inequalities in the territory. Rather, it allows to expose historic vulnerabilities while creating new ones.

Source: Arturo Silva Lucas.

These spatial inequalities are recognized in the characteristic coastal residential complex or "gated community" as it is customary to call it on the Pacific coast, although it’s not exclusive to residential complexes. These are self-segregated spaces in which services are guaranteed on many occasions outside the rest of the receiving community. For example, high-speed Internet, private transportation outside the town, private access to the beach, security and private sources of drinking water, and amenities such as large green areas, swimming pools, marinas, exclusive sports infrastructure, etc.

When the real estate sector discovers new beaches, it’s common for the native inhabitants to be the ones who point out an irregular management of local water sources to supply new housing projects. Also, in the first stages of investment there is evidence of a high concentration of land or municipal concessions of the Terrestrial Maritime Zone (ZMT). See the cases of Marbella in Santa Cruzor the beaches of El Jobo and Rajada in the Guanacaste canton of La Cruz. In the latter, the municipality itself has pointed out an abnormal concentration of concessions in the hands of few real estate developers (Municipalidad de La Cruz, 2020)

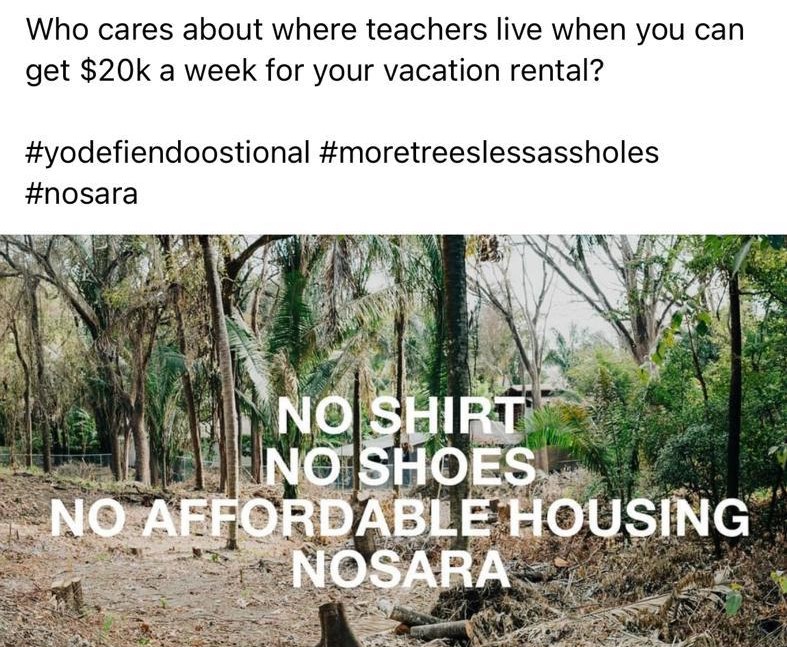

The lack of territorial planning or regulation of the real estate market is evident in investment niches with more advanced stages. Apart from urban saturation, pollution and poor water management, new problems associated with first world cities appear. It seems strange, but in coastal destinations like Nosara, affordable housing is a problem that resident tourists already point out. This does not stop drawing attention because this population group has remained on the sidelines of discussions about residential tourism. Possibly because there is already a segment of that group that sees its lifestyle threatened. In Nosara, the urgency of regulating new coastal constructions is discussed due to the threat it poses to the Ostional Wildlife Refuge.

Source: Facebook.

Tourism representatives of destinations surrounded by residential tourism have not expressed concern about the implications of greater demand for tourist housing. Such is the case of the aforementioned Tamarindo beach. There, Hernán Imhoff, representative of the Chamber of Tourism finds “inexplicable the delay of the regulation statute, given the thousands of jobs that digital nomads are going to bring”. In contrast, a 2021 study identified Tamarindo's unsustainable real estate growth as the cause of contamination in Las Baulas National Marine Park.

Imhoff, along with Hernán Bignani, is the representative for Guanacaste in CANATUR according to their website. Bignani, for his part, is the general manager of W Costa Rica & Westin Reserva Conchal, an all-inclusive resort that, despite the pandemic and the destruction of tourism jobs, had profits of 4.8 million dollars in 2020 as a result of its sales of residential units.

The debt always pending

Residential tourism does not enjoy the attention of national authorities nor its part of the construction of public policy. The ICT, despite sharing leadership in the design of coastal regulatory plans, does not take residential tourism into account in its periodic reports or public databases. In fact, there is a significant delay in drafting or updating coastal regulatory plans without, to date, recognizing an interest in advancing in this direction. It is clear that the profile of the digital nomad targeted by the new law does not seek to use hotels, but instead tourism housing for long stays.

Tourism is a ground-level activity. Just as tourism cannot be understood if its context is not taken into account, neither can public policy be written out of context. Law 22,215 for the attraction of digital nomads has a tint more like a commercial treaty that deals with tax and customs aspects for the entry of foreign currency than tourism itself. The presence of the digital nomad is certainly not new in many destinations in Costa Rica. It could be said that it has been fundamentally a seasonal offer that has ignored the daily realities where it takes place, especially in regions that have expressed criticism of certain aspects of tourist activity.

The pandemic has allowed a realignment of the groups in favor of a greater presence of the large business chambers linked to the production of urban land on the coasts. Not long ago in the Legislative Assembly, the proposal to liberalize the ZMTwas discussed so that external actors could be concessionaires of the coastal strip more easily. If measures are not taken in time that is based on dialogue with the people who inhabit these tourist spaces and the institutions that carry out cross-control, the tourist conflict in Costa Rica will be reproduced with greater intensity. Although at the moment this problem seems to have more attention outside the country than inside it.