12-07-2020

COVID-19 outbreak on Diamond Princess cruise ship: what lessons could we learn?

Angela Teberga | Alba SudThe Diamond Princess has been pointed out by academic literature as the only cruise ship in which the origin and evolution of the contagion could be mapped. Due to its importance, we can reconstruct what we know about this experience.

Photography by: Bernard Spragg, under creative commons license.

As we wrote in the previous article, a significant number of cases and outbreaks of the new coronavirus has been recorded around the world. Among them, the biggest outbreaks happened on the Ruby Princess and Diamond Princess cruise ships. Although the outbreak of COVID-19 contamination in Ruby Princess was the largest recorded in absolute numbers (852 infected and 22 deaths), the extensive literature of international infectology journals’ articles about the COVID-19 on cruise ships gives more emphasis to the Diamond Princess, where the first outbreak happened, and also the only one in which it was possible to trace the origin and evolution of the contamination.

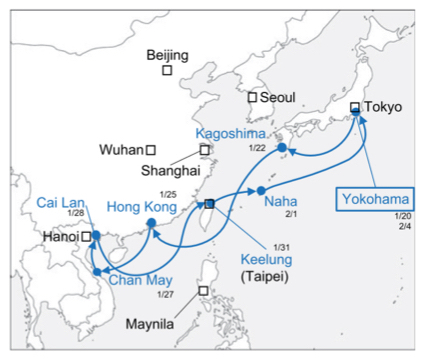

The Diamond Princess cruise ship departed on January 20, 2020, from Yokohama (Japan), for a tour through Southeast Asia. The trip included stops in China, Vietnam and Taiwan (See picture 1). Five days later, on January 25, a passenger with symptoms of COVID-19 disembarked in Hong Kong, but the ship's operations continued. The ship returned to Japan only in the first days of February, when the first disembarked passenger had his test for COVID-19 confirmed. The ship remained in Yokohama for the following weeks.

Picture 1 – Itinerary of Diamond Princess ship from January 20 to February 4

Source: Nakazawa et al. (2020)

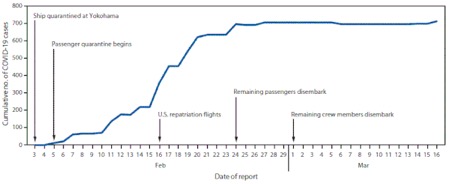

In Japan, the ship was already quarentined when tests were performed among symptomatic people on board, and positive testing for the new coronavirus was growing exponentially (see on picture 2 the period between the 5th and 24th of February). Dahl (2020) estimates that, at the time, the ship may have had the highest concentration of cases outside mainland China. Also, according to John Hopkins University monitoring, the ship presented more contaminated people than other countries’ numbers of cases in the present moment [June 17th], being ahead of São Tomé and Príncipe, Malta, Mozambique, Jamaica, Liberia, Taiwan, Vietnam, Suriname, Syria, Angola, Cambodia, and others.

Picture 2 –Cummulative number of confirmed cases on Diamond Princess

Source: CDC.

Altogether, it was registered that 19.2% of the Diamond Princess’ embarked people were contaminated by the new coronavirus. Of the 712 who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, 331 (46.5%) were asymptomatic at the time of testing. Among the symptomatics, 37 (9.7%) required intensive care (Moriarty et al., 2020). The cases were verified among people from 28 different nationalities, with emphasis on the Japanese (42%), Americans (13%), Chinese (9%), Filipinos (8%), Canadians (8%) and Australians (7%) (Mizumoto et al., 2020).

According to Takeuchi (2020), passengers and crew members who needed hospitalization were admitted to the emergency medical facilities of Yokohama City (Japan). Some patients with stable respiratory condition at the time of disembarkation had their health gradually deteriorated, requiring lung ventilators and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Nishiura (2020) estimates that the peak of the transmission occurred between February 2 and 4 and that the estimated number of new infections among passengers without close contact after February 5, when quarantine was imposed on the ship, was quite small, reaching a maximum of one case of infection per day from February 8 to 10. That’s why the author states that the policy of restricting circulation within the ship has succeeded in significantly reducing the number of secondary transmissions on board. Most deaths were recorded, according to Russell et al. (2020), between February 21 and March 2.

The Japanese government's decision to keep passengers quarentined on board for fourteen days, from February 5 to 19, instead of disembarking and repatriating them immediately, was intended to protect the population on land, regardless of the consequences for those on board (Dahl, 2020). Takeuchi (2020), a physician at Yokohoma University's Emergency Medical Department, said in mid-February that nine (9) emergency medical centers in the city were already occupied with Diamond Princess passengers, so "This is one of the greatest concerns regarding the future increase in the number of patients from the City" (Takeuchi, 2020, p. 3).

Nakazawa et al. (2020) present a reflection about the quarantine imposed by the Japanese government to the people on board of the Diamond Princess. The authors understand that there has been an ethical dilemma between imposing isolation on the ship and accepting the disembarkation of passengers for treatment or isolation on land. "The dilemma between isolation and human rights is a classic and fundamental issue in public health ethics, and, thus, it is difficult to propose concrete arguments that solve the dilemma completely" (Nakazawa et al., 2020, p. 4). They conclude by stating that decision-making must take into account the geopolitical considerations and agreements and the availability of medical resources and health facilities to care for those infected.

Sawano et al. (2020) believe that the quarantine imposed was a mistake for three main reasons: 1) It was not effective enough to avoid spreading the virus in Japan, since there were already cases of infected people in its territory before the arrival of Diamond Princess; 2) It may have contributed to accelerate the contagion of the virus among the ship’s passengers and crew; and 3) The medical and psychological care for passengers and crew was unsatisfactory, especially taking into account that most of the them were elderly, with more than 200 people over 80 years old.

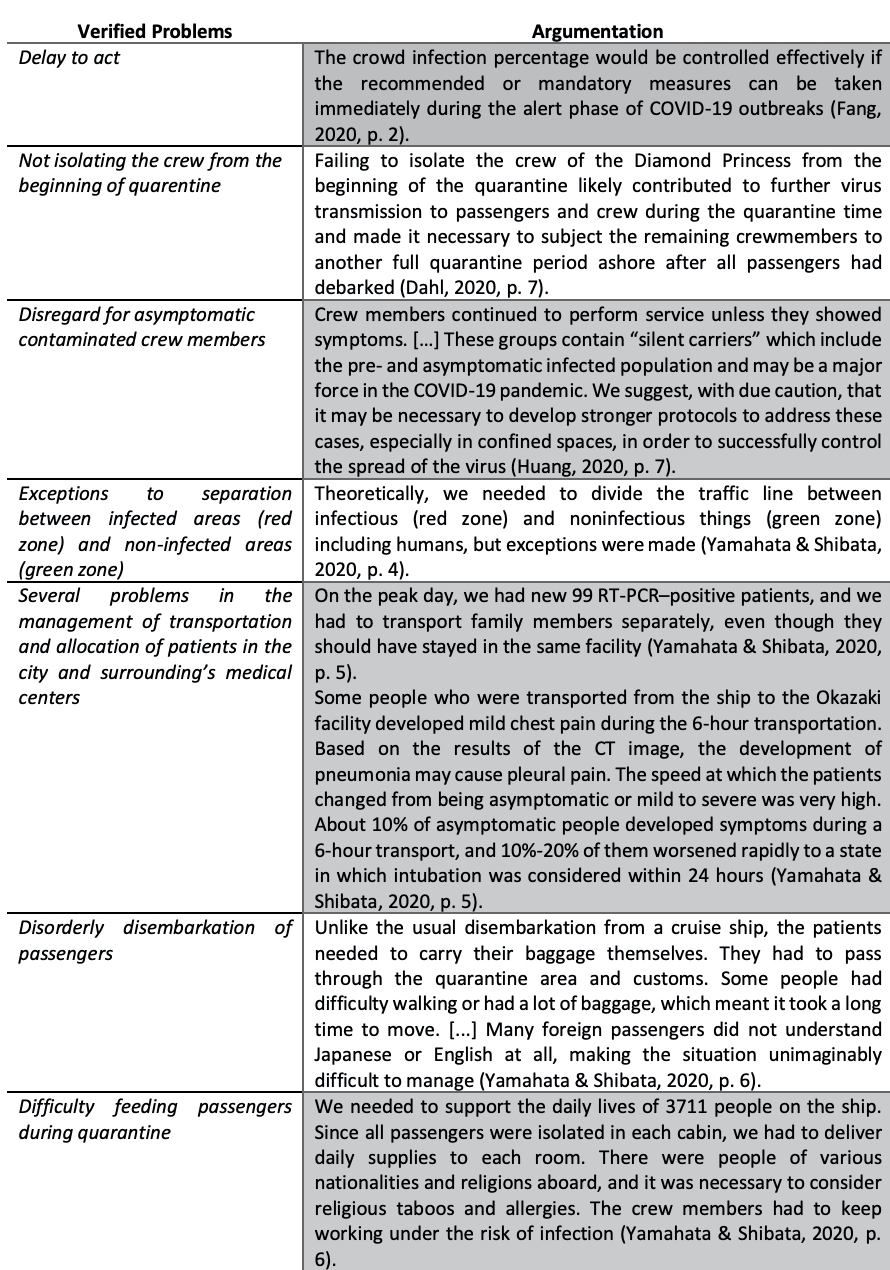

In fact, the outbreak on the Diamond Princess ship caught the attention of infectologists from all over the world, who made harsh criticisms about the outbreak’s prevention and management measures. The international press highlighted the criticism of Kentaro Iwata, a professor in the infectious diseases division of the Kobe University Hospital (Japan), who declared in an internet video, deleted soon afterwards its publication, that there was no clear separation of uncontaminated "green zones" from potentially dangerous "red zones" inside the ship.

The literature notes also came in the same direction. In table 1, we present the main arguments.

Table 1 – Verified problems in the prevention and management measures of the COVID-19 outbreak in Diamond Princess

Source: organized by the author.

We recall that the academic literature about the occurrence of communicable diseases on cruise ships has been privileging the focus on the passengers, or even on all the embarked, indiscriminatedly. Regarding the outbreak of COVID-19 in the Diamond Princess, we found only two papers that specifically refer to the contamination among the crew (Moriarty et al., 2020; Kakimoto et al., 2020). Even so, it was not possible to find any official data on the amount of contaminated crew members among the 712 confirmations, as well as on the amount of deceased crew members among the 14 recorded deaths.

Moriarty et al. (2020) describe the profile of the total Diamond Princess workers, 1,045 crew members. On average, they were 36 years old; they were from 48 different nationalities: 51% from the Philippines, 13% from India, 7% from Indonesia and 29% from other countries; 81% of them were men and 19% were women.

Kakimoto et al. (2020) presented in their paper an initial investigation about the transmission of the new coronavirus among the crew members during the quarantine of the Diamond Princess ship. The first confirmed case was a crew member from the food sector who presented a fever on February 2, and, after laboratory confirmation, was released for treatment on land. Until the end of the first week of February, only the crew members who sought the ship's medical assistance presenting COVID-19 similar symptoms had access to laboratory testing. From that day on, many other cases were confirmed among the crew.

The data presented in the article confirm the thesis that the transmission of the disease is related to the fact that ships brings a large amount of people together into confinement. It was found that, at the time of the investigation, 15 of the 20 confirmed cases occurred among food service workers who prepared food for other crew members ("crew mess") and passengers; and 16 of the 20 confirmed cases occurred among the cabins on Deck 3, the floor where the food service workers lived.

These interviews indicated that infection had apparently spread among persons whose cabins were on the same deck and who worked in the same occupational group, probably through contact or droplet spread, which is consistent with current understanding of COVID-19 transmission (Kakimoto et al., 2020, p. 312).

Again, as in the introductory article, in which we presented general studies about outbreaks of diseases in cruise ships, the authors Mizumoto et al. (2020) point out that the transmission of the new coronavirus (whose power of contagion is high, especially in confined spaces) on cruise ships, and especially on the Diamond Princess, could have been mitigated if there wasn't a high concentration of people. "To further mitigate transmission of COVID-19 and bring the epidemic under control in areas with active transmission, it may be necessary to minimise the number of gatherings in confined settings" (Mizumoto et al., 2020, p. 4).