22-06-2020

LGBTIQ community and tourism: between capital and life

Núria Abellan | Alba SudIn the relationship between the LGBTIQ community and tourism the commodification of these identities has prevailed. This has impacted on how destinations approach the community, often setting aside the difficulties suffered and the differences.

Crédito Fotografía: Bandera del colectivo LGTBIQ. Fuente: Stock Catalog, bajo licencia creative commons.

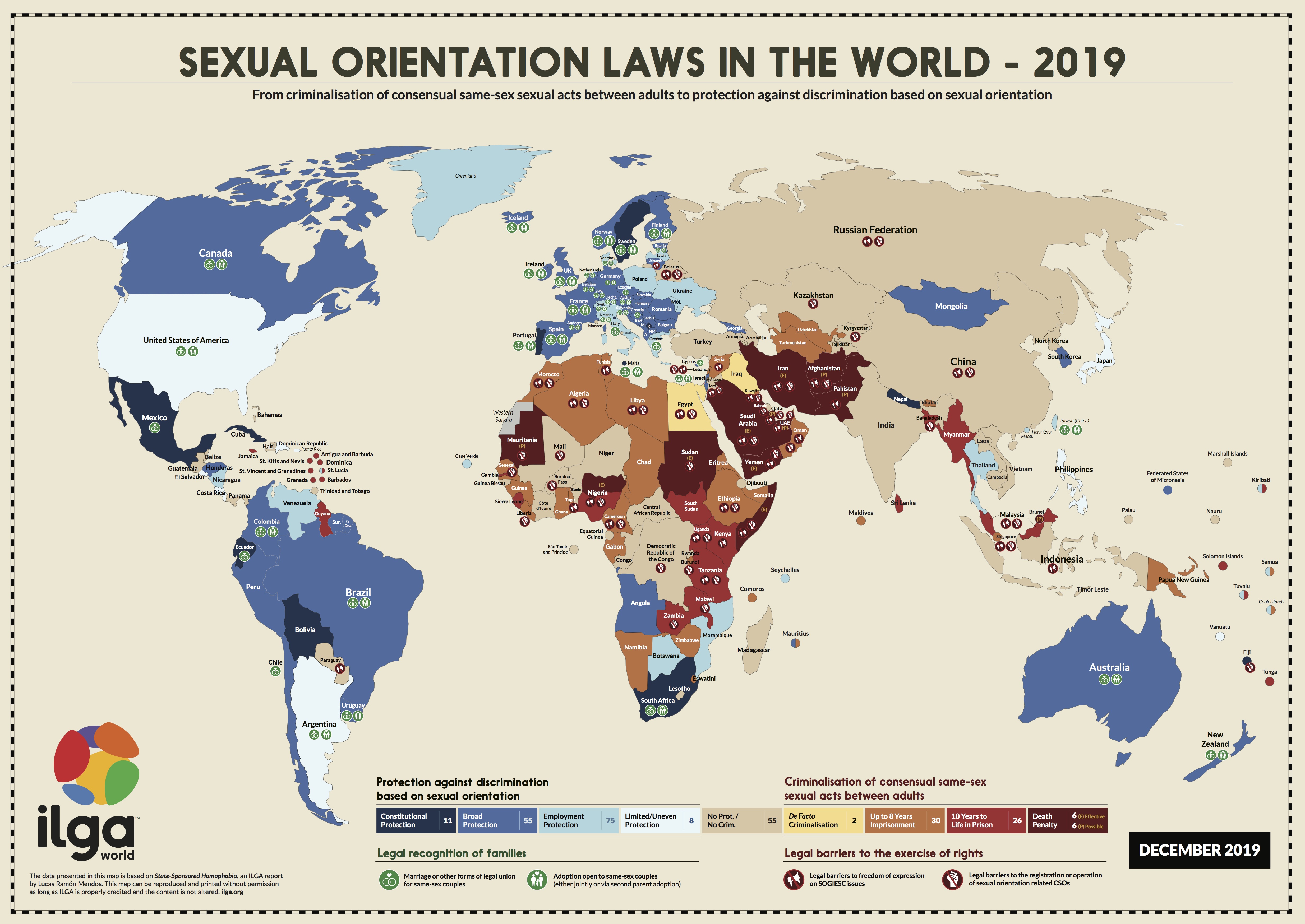

The LGBTIQ community is composed of all those individuals whose sexual orientation and/or gender identity are considered outside the cisheterosexual norm. This way, the acronym LGBTIQ, despite the debates and controversies to establish it, includes lesbians, gays, bisexuals, trans, intersexuals, queer people, and all those orientations and identities socially marginalised and oppressed. Even though the rights of the LGBTIQ community have increased over the years, data proves they still suffer discrimination. In this sense, the Report on Homophobia 2019, developed by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), highlights some data around the world: 11 countries specifically mention the rights of the community in their constitution, 55 cover broad protections, and 75 countries guarantee protection in the labour market. On the other hand, 30 countries count with sentences of up to 8 years of prison for those who are LGBTIQ, 26 other countries up to 10 years of imprisonment, and a total of 12 countries include the death penalty for those who are part of the community. The same report warns that other rights need to be analysed, such as marriage, the possibility to adopt, and the access to name registration changes and/or physical treatments for trans people; while emphasising prohibitions such as the right to protest and freedom of expression. Moreover, it is necessary to outline that, despite their great importance, the rights guaranteed by law may not correspond with the social realities of the LGBTIQ community.

Laws regarding the LGBTIQ community around the globe, December 2019. Source: ILGA, under creative commons license.

Understanding the diversity in the community, it is necessary to establish the difference between sex and gender. Sex is the compilation of biologic and physiologic characteristics through which individuals are divided into male and female and, therefore, into men and women. On the other hand, as defined in the Chrysallis Association, gender is a social construct, a set of characteristics socially and culturally adopted, as an expression and manifestation of the gender identity. Thus, in the case of a match between the biologic sex and the gender assigned at birth, we talk about cisgender people; while in the case of biologic sex and the gender assigned at birth not coinciding, we talk about trans people.

Thereupon, it becomes apparent that this community is not homogeneous, since there is a great number of identities, orientations, experiences, and diverse oppressions. For this reason, it is not possible to treat the LGBTIQ community as one unique group, but rather the individual experiences are determined greatly by the imposed social barriers. For instance, understanding the patriarchal conformation of societies, inside the community, women have suffered historical invisibility that has led to gay men being identified with the total of the community or to them having a greater presence, both answering and reproducing patriarchal dynamics.

An example of historical inequality among the LGBTIQ community is South Africa, where gender and race have a great influence. In this sense, Cape Town demonstrates that the spread image of those who are part of the LGBTIQ community does not match reality, since it has been established the white man, young and middle-class as the prime agent. Constructing the hegemonic model based on this image entails making race and other identities invisible (Reygan, 2016), and, therefore, the problematics that other people have to face too, as the case of corrective rapes on lesbians. On the other hand, the experiences of a trans gay man may have little in common with the ones of a cis gay man, the same way that race, age, social class or the matching or not with the beauty cannons need to be kept in mind, among many other oppressions.

Origins of the duality LGBTIQ community and tourism

Except for names such as Oscar Wilde or Lord Byron, little is known regarding the historical relationship between the community and tourism. In fact, it is not approximately until de 1920s that some destinations open to receiving mainly gay tourists, all of them with great economic power, appear, as is the case of Schöneberg neighbourhood, in Berlin; Sitges, in Catalonia; Mykonos, in Greece, or until the 1940s as is the case of Fire Island, in New York or Provincetown, in Massachusetts (Silva, Cardoso and Barbosa, 2018). These destinations were not publicly promoted as such, but they were known among the gay community as safe spaces that allowed them to live as they desired. Vacations offered these men the possibility to build a homosexual identity that they could not live anywhere else. In other words, due to the social rejection they suffered, they were obliged to search for a gay space so they could live with the normality they could otherwise not find (Puar, 2002).

Sculpture in honour of the homosexual community in Sitges, Catalonia. Source: Dos Manzanas, under creative commons license.

For this reason, in 1963 Bob Damron, a businessman in the United States, published The Address Book, a guide on neighbourhoods, bars, restaurants, and other safe shops for gay men. This resource changed frequently, both due to the opening of new businesses and for having to erase others that police harassment forced to shut down. On June 28th, 1969, the Stonewall riots took place in New York, when a police raid entered the Stonewall Inn, a bar well-known and frequented by the LGBTIQ community. Form this moment on, divergent gender identities and sexual orientations became a lot more visible and, therefore, despite the difficulties and threats, more possibilities to travel existed. It is in this new scenario that in 1972, geographer Hanns Ebensten founded the first tour operator targeting exclusively the G community, especially white, Global North, and with notable purchase power. Since then, diverse initiatives and destinations openly welcome to LGBTIQ visitors emerged, such as the first LGBTIQ tour to Israel in 1979 or the first Gay Games in San Francisco in 1982.

A year later, in 1983, the International Gay Travel Association (IGTA) was created, derived from travel agencies and accommodation services established in the United States, although it was not until 1997 that the L was added in order to be the International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association (IGLTA). This organisation was created with the mission of giving information to LGBTIQ tourists around the world and, at the same time, demonstrating their social and economic impact with the aim of expanding tourism throughout the globe. Over its years of history, IGLTA has promoted initiatives such as RSVP, an exclusive cruise for gay men in 1983 or the first cruise for lesbians in 1990, by Olivia Cruises. Because of this growth, the gay community, and therefore a part of the LGBTIQ as well, became a new market niche that was considered to be at its finest moment, when homosexual identities are equated to high purchase power (Puar, 2002).

The emergence of this tourism market is united in 1994 by the first marketing campaigns dedicated exclusively to attract LGBTIQ public, in this case to Montreal, Quebec. These were followed by the ones developed by American Airlines, in which the employee resource group GLEAM, devoted to the promotion of good practices, awareness and equal rights for every LGBTIQ person, either worker or tourist. From these milestones on, companies and events regarding tourism and the LGBTIQ community multiply in such a rhythm that it is no longer possible to keep track of them and establish a chronology. It was also the moment when Pride Parades, held on June 28th, gained international strength. In fact, InterPride states in their last report that in 2017, a total of 971 parades were held around the world. The same report illustrates the polemics surrounding these events among the LGBTIQ community, both for their transformation from a political stand to a commercial festivity, and for the domination of the G community, which is the most frequent criticism. This is how it becomes clear that the acronym is extremely varied and, thus, the perceptions of every integrant conforming it must be taken into account (Ram et al., 2019).

The LGBTIQ community and tourism nowadays

The academic study of the LGBTIQ community concerning tourism begins in the 90’s, with a scope of research focused mainly on gay, white men, with no children, from the Global North, residing in urban areas and with a high purchase power; skewing the global knowledge (Vorobjovas-Pinta and Hardy, 2015). On the other hand, the topics studied are basically pride parades, or events created specifically for the LGBTIQ community, such as sports events. Throughout the years the investigations have broadened, reaching more identities and other aspects, and is currently growing exponentially. As the LGBTIQ community has been more visible in the tourism field, two main positions have emerged to study this topic. The first one, from a business perspective, tends to analyse the community as a market niche, and so studies revolve around the motivations and preferences of those who go on a trip or who may be potential visitors, as well as research on improving marketing strategies and the attraction of tourists. From this view, one of the facts considered of greater importance is the total of 36 million stays that are accredited to LGBTIQ tourists in 2016 (OMT, 2017).

The second one, from a critical point of view, focuses on the analysis of experiences of LGBTIQ people who travel or who are part of the local community and who are in contact with tourism. Under the umbrella of this perspective, the attempts of commodifying LGBTIQ identities are debated. This willingness to attract the LGBTIQ community has led a huge number of destinations and companies to incorporate pinkwashing, which is understood as a set of political and marketing strategies that call upon the kindness to the community. This term is specifically used for the face washing of Israel, which broadcasts an image of liberal and democratic state through showing its support to the young, gay man who respects the beauty cannons established (Hartal, 2018); to deflect attention from the human rights violation of the Palestinian people.

Bus of the accommodation business Booking taking part in the 2018 London Pride. Source: Michelle Claire Woolnough, under creative commons license.

Therefore, it is of vital importance to identify what impacts each of these positions may have upon tourism, as well as highlighting which vision succeeds in setting the lines of work for the industry. The World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) and the European Travel Commission (ETC) are the two strongest lobbies in the sector, who work together with IGLTA to get closer to this community. From this union, three different documents have been created, respectively: two Global Reports on LGBT Tourism (2012 and 2017), and the Handbook on the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) travel segment, all of them conceiving LGBTIQ tourism as a market niche in international expansion and as an economic growth opportunity through offering specialised services. This conception is known as pink capitalism, that is, the incorporation of LGBTIQ identities in the market economy to extract monetary profit (Silva, Cardoso and Barbosa, 2018), linked to the idea of pink money, understood as the purchasing power of the community.

With this perspective in mind and with the current knowledge voluntarily biased, the literature review of fifty articles by Vorobjovas-Pinta and Hardy (2015), concludes that, following the line set by the UNWTO, the vast majority of publications are centred on the offer and the demand of resources, but social aspects are excluded. In this sense, the most valued characteristics of the LGBTIQ tourists are diverse, but all of them related to the economic benefit for the destinations. It is considered that many homosexual couples are DINK (Dual Income No Kids), which allows them to travel during low season, with a higher frequency, and often to tourism destinations that are not overcrowded to avoid family destinations (Silva, Cardoso and Barbosa, 2018). Apart from this economic profile favourable for the destinations, one of the most appreciated aspects by the UNWTO and the ETC is the industry involving pre-marriage celebrations, weddings, and honeymoons, which instead of being read as a conquest of rights are seen as income.

The data provided in October 2019 by the 24th Annual LGBTQ Tourism & Hospitality Survey, from Community Marketing & Insights, a company based in the United States, proves that treating the community as one whole does not correspond with its complex reality. In this study, the respondents are divided into three groups: homosexual and bisexual men, lesbian and bisexual women, and trans and non-binary people. All three groups express that the main motivations to choose a destination are safety and it being LGBTIQ-friendly. The differences are mainly found in the motivations of gay and bisexual men and trans people to travel to destinations considered an LGBTIQ hotspot (37% and 35% respectively), while this motivation is determinant for just 23% of lesbians. These facts go with the preference of G and B men for urban destinations with a vibrant activity (64%), which contrasts with 39% of L and B women and 42% of trans visitors. Therefore, the activities chosen by each group also vary, especially in visits to areas known as LGBTIQ, more popular among G and B men, but even more regarding LGBTIQ nightlife (50% of G and B men, 32% trans people, 28% L and B women). These preferences go accordingly with the self-perception of those who travel: a 45% of G and B men consider themselves LGBTIQ tourists, while this same perception is a 32% for trans visitors and 28% of L and B women.

Stonewall Inn, in New York. Source: Travis Wise, under creative commons license.

These facts show that the interests and behaviour of tourists make gay and bisexual men the main users of services and businesses exclusively directed to the community, and that is the reason why they are the group with a higher expenditure in the activities created specifically for this market niche. In this sense, the tourism industry is legitimised when reinforcing the equating of the LGBTIQ community to gay men, since they are the ones that provide a greater economic benefit, making other identities with a profile considered traditional invisible, as they are not considered suitable to be commodified. This is especially the case of lesbian and bisexual women, who show greater interest in family activities and are less self-identified with being LGBTIQ tourists. Moreover, the existence of the “good homosexual” image is displayed in marketing campaigns all over the world, while people who do not fit in this cannon enjoy less social acceptation and, thus, more insecurity and invisibility (Puar, 2002), fractioning the complex LGBTIQ community into accepted and rejected identities.

Final thoughts

The increase experimented by LGBTIQ tourism and the forecasts of its growth as new regions become tolerant to this public is a good reason to celebrate, since it is the demonstration that more territories are considered safe (Silva, Cardoso and Barbosa, 2018). Despite this, the business perspective applied to this reality aims to overlook the gaps in the geography where LGBTIQ people are disregarded. In fact, UNWTO affirms that encouraging tourists to broaden horizons and visit places where they are not welcome is necessary, arguing that the transformative power of their presence may lead to some changes in the destination (UNWTO, 2017). This conception is linked to the decision of IGLTA of not boycotting neither companies nor destinations that discriminate against the LGBTIQ population, affirming that this action may have a negative effect upon the local community. Both positions denote that the willingness to open new markets is considered more important than the safety and the experiences of LGBTIQ tourists.

Similarly, UNWTO and ETC highlight marriage equality, emphasising that every country that legalises these unions involves millions of euros on income for the tourism industry, taking into account LGBTIQ identities exclusively when they may be commodified and transformed into a profitable niche market. To be able to discern “LGBTIQ” and “profitability”, the studies involving the community and tourism must be developed from social studies, stepping away from the business perspective that turns them into a business opportunity. From this scope, it is essential to fill the gaps that the production of a biased knowledge production now leaves. These shortages revolve around aspects such as the safety of the traveller, the experience and the sensations experimented, or understanding the inclusion and exclusion dynamics, in other words, it is necessary to problematize the tourism of the LGBTIQ community and refuse the idea that the presence of the community is a seal of quality for the destination.

On the other hand, the differences among the diverse identities present in the acronym need to be analysed, since nowadays, the experiences of gay men are standardised as the ones of the whole community. The importance of the G community from the beginning, which currently holds the hegemony, involves that the study and approximation to the sector are done from a concrete and marginalising prism, favouring certain logics that leave behind diverse identities and social aspects. This means ignoring dynamics present in the industry that allegedly give a bad image, as is the case of sex tourism of men who have sex with other men, motivation listed by 20% of G and B men, 8% of trans people, and 1% of L and B women (CMI, 2019).

Likewise, intersectionality ought to be put in the centre in order to understand how other variables interact with gender identities and sexual orientations, since LGBTIQ tourism is not related to numbers, but rather to lives. Some of the aspects in need of further investigation are the experiences of seniors; stigmas, difficulties and fears that may experience trans travellers; race; or understanding how the creation of images of the destinations affects the whole LGBTIQ population.